- Markets Mirage

- Posts

- One week / one topic: Magic money trees

One week / one topic: Magic money trees

How to spend money you don’t have

What happened?

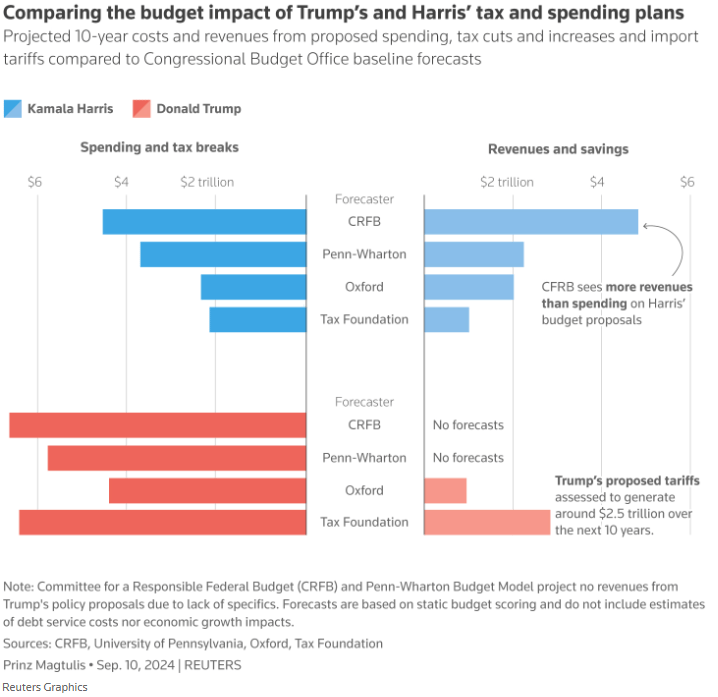

As per the last debate, Donald Trump’s spending plans (the election is essentially still a toss-up) could add up to $7 trillion to US primary deficits over 10 years

To address the EU’s ‘existential challenge’, Mario Draghi’s spending recommendations are equivalent to an unprecedented 5% of GDP (i.e. double the post-WWII Marshall plan)

After all, what’s an extra few trillion among friends?

Humans respond to incentives, and so political leaders are constantly tempted to think: ‘let me borrow as much as I can to achieve my goals (usually, being re-elected), because it will be my successors’ problem anyway when the bills come due…’.

For the ones with even fewer scruples, there is also this corollary: ‘Wait: by saddling the ‘enemy’ with extra debt, their life will more difficult once in office and they will fail… so my side can return to power sooner. Win-win!”

As we careen towards more and more debt, the Washington consensus – free trade, privatization, central bank independence, fiscal prudence and fiscal policy becoming apolitical – seems dead and buried. (Suggested reading)

For a long time, advocates of the ‘old regime’ feared that markets had become addicted the ‘Fed put’. How quaint…

With the Covid response, we have entered new territory and (re-)introduced the ‘fiscal put’, where – as it turns out – there actually are magic money trees if you look hard enough.

You just (might) have to pay for it at some point…

However – while you can’t really trade government bonds based on long-term fiscal projections, since there are no deficits hawks in the foxholes of a financial crisis – this feels precisely like the kind of thing that doesn’t’ matter… until it does, suddenly!

Given the central role of developed markets government bonds in portfolios, what should then investors make of these recent developments?

Are US Treasuries (primarily) and German Bunds becoming less attractive?

Our observations

Fundamentals: To some extent, giant debt burdens and devil-may-care borrowing intentions shouldn’t matter in the short term for high-quality, sovereign borrowers. That said, after Covid we seem to have entered a new era of profligacy and the trend remains worrisome.

Price action: Not much to see here as of late, which is interesting in and of itself. Bar a few minor auction-related wobbles, investors seem uninterested and yields have actually been coming down.

Investor beliefs: While it’s common knowledge that the word ‘austerity’ is taboo for politicians, there is still a readily available narrative about ‘runaway, unsustainable debt’ that could quickly take hold should yields jump in a classic narrative-following-price self-fulfilling loop. (‘higher for longer’, anyone?)

So what?

While we continue to believe in high-quality government bonds as valuable portfolio insurance, we need to nonetheless be aware of ballooning deficits and runaway debt levels.

With that in mind, the words of Chuck Prince (former CEO of Citi back in 2007) come to mind somehow as a powerful cautionary tale, given what happened shortly afterwards with the Global Financial Crisis: "As long as the music is playing, you've got to get up and dance. We're still dancing.”

Now that inflation has been retreating for a while and central banks have started (or are preparing) to cut rates, we are also reminded that powerful disinflationary forces remain in place in the form of technological advancement, demographic change and (yes, still) globalization.

Government bonds therefore still offer attractive asymmetry at current yield levels, and we maintain our positions with the dual objectives of generating attractive income levels and counterbalancing equity risk.